Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings

Public Affairs

Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

31.10.20—30.01.21

RM ‘Gay Liberation’ is a term haunted by a type of nostalgic hippydom, a place where history‘s popular imaginations (and by that I mean the middling heterosexual status quo) like to believe that equality has reached an apex of non-threatening assimilation, almost as if the fight is over. With your work you take a biting focus on how this is far from the truth and like the rest of the world, it is powered by the white, non-effeminate and hyper essentialist male libido leaving the rest of this so-called community well and truly behind. What can be expected with your upcoming show at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi?

H&R Our new show is called Public Affairs, a phrase derived from the Latin Res Publica, the etymology of Republic, the name of our first fresco that we made for our recent exhibition

In My Room at Focal Point Gallery. In many ways the concerns of the shows are connected, loosely. In My Room explored how a culture

of male sex in public and mens-only gay bars linked to a broader culture of (white) male dominance socially, symbolically, historically, culturally and architecturally.

RM You have told me that this show will take an intricate look at how law and non- heterosexual love become entangled. Could you tell us more about the plans for how these concepts have evolved?

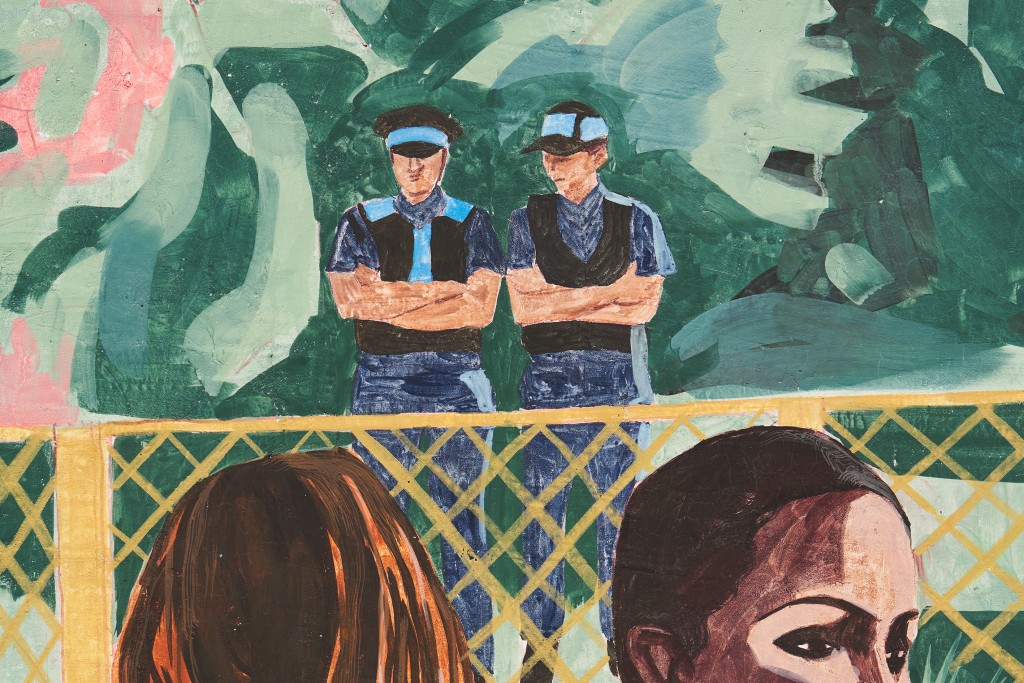

H&R For Public Affairs we were thinking more specifically about hate crime legislation. The fear and threat of violence became a unifying force amongst LGBTQ activists in the late 80s and 90s. Gay advocacy groups such as the Gay and Lesbian Alliance against Defamation in the USA have been accused of racism for amplifying white and male voices at the expense of people of colour and for not including violence against trans people in their definition of bias. Not only has this had the affect of increasing the legal privileges of white and cis-gendered people but it has also increased the power of the police, led to more aggressive sentencing and expanded the carceral system which disproportionally incriminates non- white people from working class backgrounds. Resources channelled by LGBTQ advocacy groups and think-tanks into assimilatory poli- cies have come at the expense of radical forms of justice aimed at dismantling, defunding and abolishing inherently anti-LGBTQ and racist structures of power.

RM Your practice mainly oscillates bet- ween drawing work that takes a painstaking amount of time depicting figurative queer landscapes that exist without time, performance and precise video work that deals with signifiers of LGBTIQA+ culture’s relationship to capitalism’s control. In your last show at Focal Point you ventured into the making of frescoes, what drew you to this new medium?

H&R We were initially drawn to fresco because materially it excited us, our drawings take many hours of obsessive work whereas fresco painting requires speed and invention, it helped us shed many of our drawing related neuroses and become less regimented in the way we approach image-making. Aside from the material pull of fresco we were interested in the role fresco has played in society and architecture.

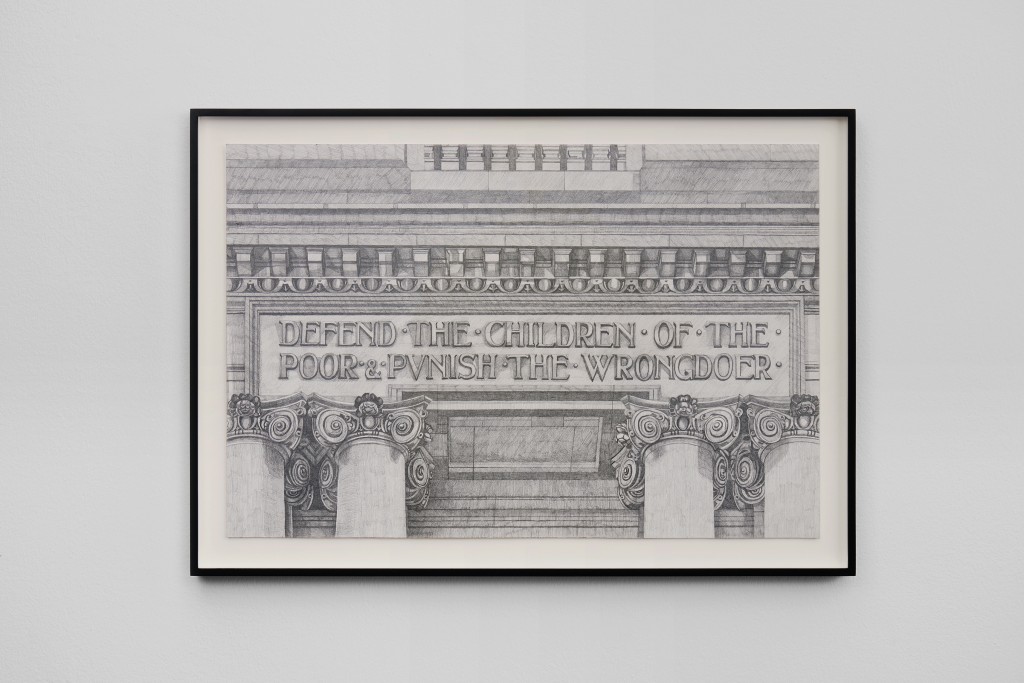

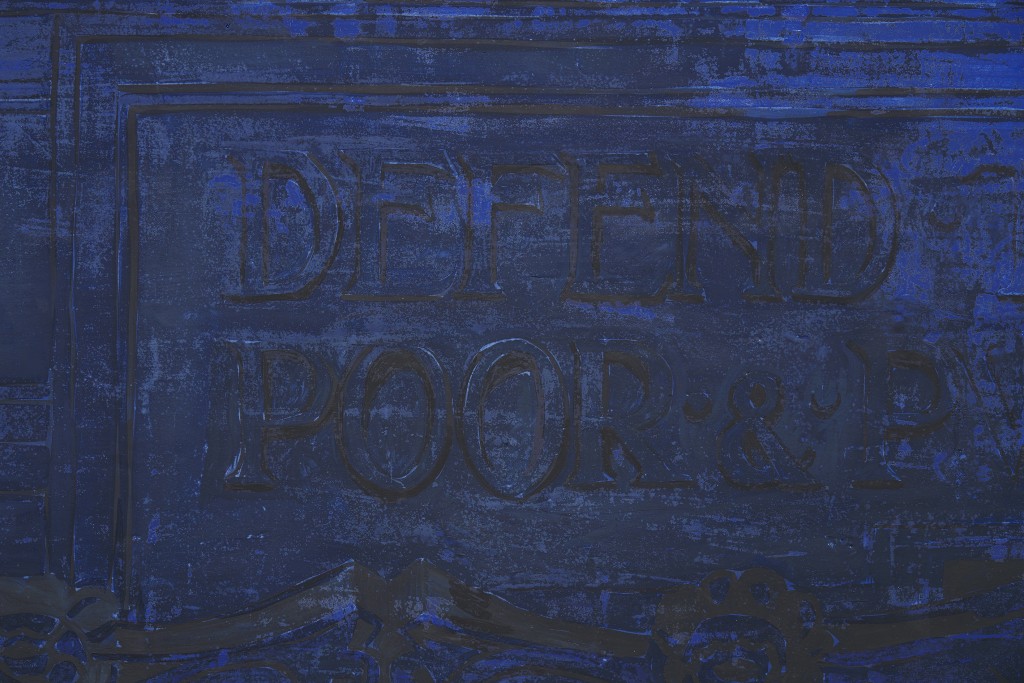

Fresco painting is often found in places of political, legal and educational importance and is executed at a monumental scale. Traditionally fresco depicts scenes loaded with ideology and symbolism whilst presenting itself as neutral or universal, often representing the moral code of the time within which it is painted, intended as instructional and educational thus reinforcing dominant perceptions. This was particularly the case in The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales (The Old Bailey), whose interiors are laden with wall-paintings depicting scenes of justice from the bible.

These images tell us a lot about the way justice along with all its baggage and biases has evolved in a western context.

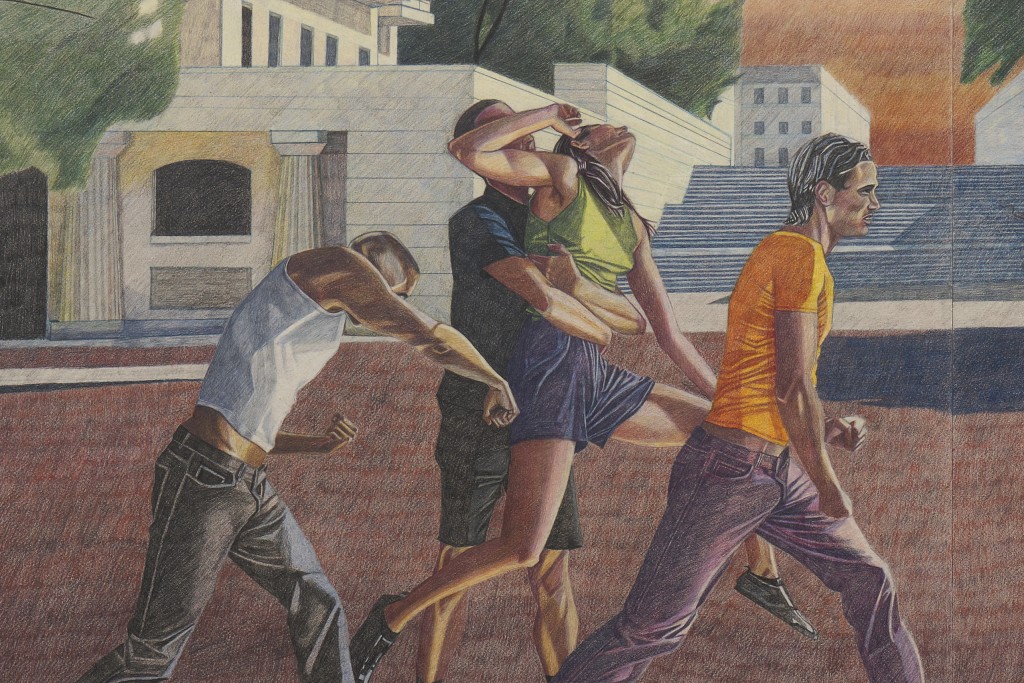

RM Your first fresco visualised an almost barren space with people in the midst of what could be both fighting and dancing, how will your new research meld into these frescoes?

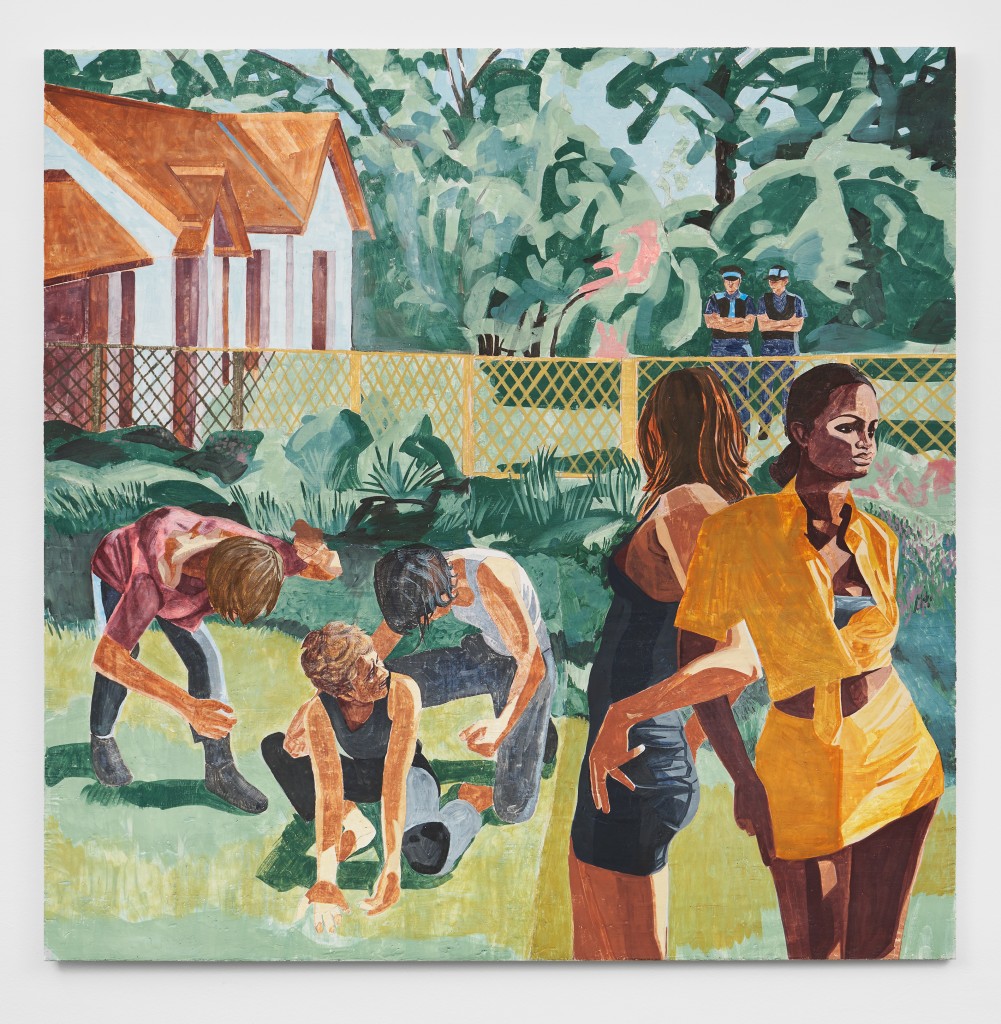

H&R There is a loose narrative that connects the work—an incident or assault and then the aftermath is shown. We do not depict any moments of actual violence and we left the characterisation intentionally ambiguous—who is the victim, who is the perpetrator? We wanted the viewer to complete the narrative, taking on the role of the judge or jury and guided by their own principles of justice.

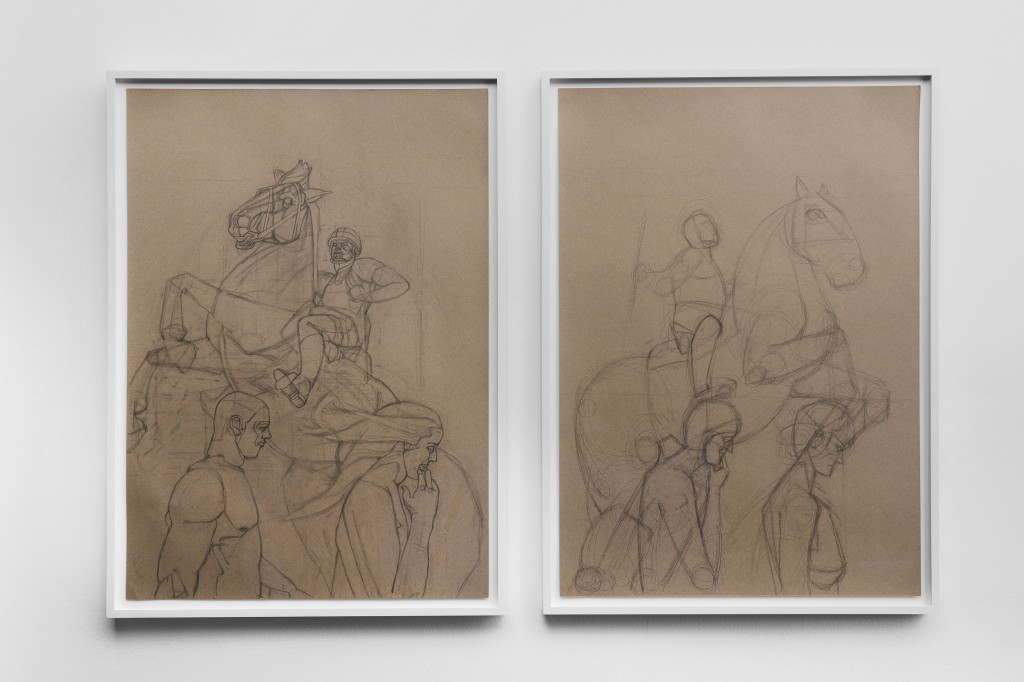

The drawing and fresco works are set in central London locations, specifically the areas in and around Green Park which we visited and photographed when it was empty during lock- down. Green Park is an area that has an immense political charge, flanked by the Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace and the Horse Guard or government, monarchy and military. Green Park is a zone of elite power but it is also the location of Gay Pride and a historic cruising ground for gay men. We were trying to make images that represent this unruly clash of registers—the disciplining power of the state and the rebellious energy of the people who gather in these spaces.

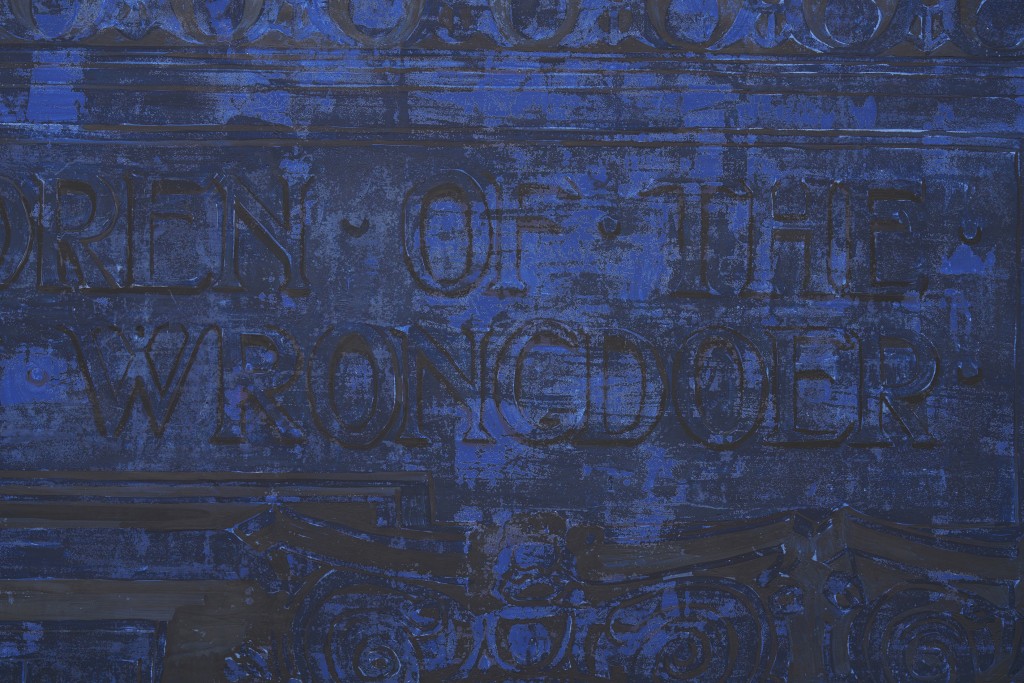

The show ends with a fresco depicting the facade of The Old Bailey which includes a sign bearing the phrase, “Defend the children of the poor and punish the wrongdoer”. We were so struck by this sign in its position of prominence over the entrance of the law court and under the statue of the blindfolded, ‘Lady Justice’ with her scales. It is an incredibly bold statement for a legal system that has systematically protected the wrongdoer and punished the children of the poor.

Excerpt from an interview between Reba Maybury and Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Kaleidoscope Magazine, Issue 36 / SS20

Contact

T +49—30—26 39 76 20

F +49—30—26 39 76 229

E info(at)bortolozzi.com

Subscribe to our newsletter here →

Schöneberger Ufer 61

10785 Berlin, Germany

Directions